Savonia Article: Role of Nurses in The Treatment of Acne in Both Healthcare Settings and At Home

This work is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

1. Introduction

Acne is a skin condition that impacts people of different age ranges. Acne is a common condition across the globe which affects nearly 9.4% of the world population. It is most prevalent among teenagers and young adults (Bhate & Williams, 2013). Apart from affecting someone’s physical appearance, acne can lead to low self-esteem, anxiety, or depression, which may require a visit to A dermatologist or health professional (Tan & Bhate, 2015).

Different types of acne can easily be treated at home using gels and creams which can be purchased over the counter. However, some acne types require professional assistance from medical experts. For example, cystic acne that cannot be treated with ordinary topical or non-prescription drugs, thereby requiring specialized treatment and should be presented to a doctor for proper treatment (Harper & Thiboutot, 2016).

Skin stuffing is another major issue in acne treatment. This is because complications such as scar formation may result in permanent dermal injury. It is, therefore, important to address this risk by seeking early professional help with the correct treatment that can assist in avoiding skin harm in the long term (Zaenglein et al., 2016).

Effective management of acne requires a good understanding of available treatments both in professional healthcare settings and at home (Ranta & Suominen, 2020). This article focuses on the role of nurses in the management of acne in the healthcare setting and at home as nurses are always or most of the time the first point of contact, also it focuses on the role of nurses in patient education, skincare routine, medication adherence, and lifestyle changes

2. Pathophysiology of Acne

2.1 Pathophysiology of Acne

Acne develops when hair follicles get blocked with sebum and dead skin cells. Several factors influence it:

1. Sebum Production: Sebaceous glands produce an oily substance called sebum that keeps the skin lubricated. Excessive production of sebum often occurring due to hormonal changes can cause pores to clog (Harper & Thiboutot, 2016).

2. Follicular Hyperkeratinization: This involves abnormal shedding of keratinocytes (skin cells) within the follicle, leading to blockage and comedone formation (Williams et al., 2012).

3. Bacterial Growth: The anaerobic bacterium Cutibacterium acnes (formerly Propionibacterium acnes) thrive in the oily environment of clogged pores causing inflammation (Zaenglein et al., 2016).

4. Inflammatory Response: Bacterial overgrowth response by body immune system from pore blocking leads to inflammation accompanied by papules, pustules, nodules or cysts (Bhate & Williams, 2013).

Figure 1: In acne there are comedones, papules and pustules. (source: terveysportti)

2.2 Types of Acne

● Comedonal Acne (Figure 2): These are Identified through blackheads (open comedones) or spots underneath the surface of the skin (zaenglein et al., 2016).

● Inflammatory Acne (Figure 3): These consist of papules (small red bumps) and pustules (pus-filled lesions) (Williams et al., 2012).

● Nodulocystic Acne (Figure 4): This is a severe form of acne with deep, painful nodules and cysts that can cause scarring (Zaenglein et al., 2016).

Figure 2: Comedonal Acne (Source: Dermstore)

Figure 3: Inflammatory Acne (Source: Dermstore)

Figure 4: Nodulocystic Acne (Source: Dermstore)

3. Treatment in Healthcare Settings and At Home

There are different treatment methods available for acne both locally and internationally. It is however important to note that care must be taken when purchasing over the counter (OTC) acne medications. This is to avoid counter-interactions.

Seeking the advice of a dermatologist or nurse should be considered properly before the use of any of the underlisted medications. In Finland, most of this OTC medication can only be gotten through a prescription by a dermatologist. They may also be found as components in other skin care products.

3.1 Treatment in Healthcare Settings

Healthcare settings align treatment plans according to acne type and severity. Dermatologists provide therapies ranging from topical acne creams up to intravenous systemic medications. (Gollnick & Krautheim, 2003).

3.1.1 Topical Treatments

Topical treatments are the mains of early-stage acne treatment. They work directly on the skin to lower production of sebum, pain as well as inflammation and bacterial colonization (Gollnick & Krautheim, 2003).

a. Retinoids: Examples: Tazarotene, Adapalene, Tretinoin.

● Mechanism: These medications change the way epithelial cells grow and develop thereby preventing formation of microcomedones and reducing inflammation (Gollnick & Krautheim, 2003).

● Application: It should be applied once daily at night. Initial irritation is common, so it is advised to start with a lower concentration and increase gradually (Zaenglein et al., 2016).

b. Topical Antibiotics: Examples: Erythromycin, Clindamycin.

● Mechanism: The antibiotics reduce Cutibacterium acnes (C.acnes)count in the skin and exhibit anti-inflammatory actions towards acne (Harper & Thiboutot, 2016).

● Usage: Often combined with benzoyl peroxide to prevent antibiotic resistance; clindamycin is typically used due to its effectiveness and tolerability profile (Williams et al., 2012).

c. Benzoyl Peroxide:

● Mechanism: Benzoyl peroxide is a highly reactive antimicrobial that kills Propionibacterium acnes bacteria quickly while it also removes excess oil from the skin surface together with dead epidermal cells (Bhate & Williams, 2013).

● Application: It comes in concentrations ranging from 2.5% to 10%, but higher concentrations do not necessarily mean increased efficacy because they can cause more irritation (Zaenglein et al., 2016).

d. Azelaic Acid:

● Mechanism: Possessing both antibacterial and anti-inflammatory activities helps normalize shedding of dead cells on the skin surface (Williams et al., 2012).

● Usage: Suitable for use in patients suffering from the early stage of acne and post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation (Harper & Thiboutot, 2016).

3.1.2 Oral Medications

Oral medications such as antibiotics are commonly used in the treatment of several types of acne which can range on different severity of its progress in a patient.

a. Oral Antibiotics: Examples: Erythromycin, Minocycline, Doxycycline.

● Mechanism: They cut down the rate at which C.acnes multiplies besides being anti-inflammatory(Zaenglein et al., 2016).

● Considerations: For a limited time, generally three to six months, to reduce antibiotic resistance (Bhate & Williams, 2013).

b. Hormonal Therapies: Examples: Spironolactone, Oral contraceptives.

● Mechanism: These medications decrease circulatory androgens leading to reduced sebum production (Harper & Thiboutot, 2016).

● Suitability: Mostly in women with hormonal acne (Williams et al., 2012).

c. Isotretinoin

● Mechanism: A potent retinol that significantly reduces sebaceous gland size and activity, normalizes follicular keratinization, and exerts anti-inflammatory effects (Gollnick & Krautheim, 2003).

● Usage: It is used to treat nodulocystic acne that has not responded to other treatments. It should be closely monitored due to potential side effects such as teratogenicity and psychiatric symptoms (Zaenglein et al., 2016).

3.1.3 Physical Treatments

Physical treatments can also be used along with medical therapies for the management of acne and improvement of skin appearance.

a. Laser and Light Therapies

● Mechanism: The application of specific wavelengths of light on C. acnes while reducing sebaceous gland activity including blue light therapy, pulsed dye lasers, photodynamic therapy respectively (Williams et al., 2012).

● Applications: It is effective against inflammatory acne and acne scars. On most occasions multiple sessions are required to achieve optimality (Harper & Thiboutot, 2016).

b. Chemical Peels

● Mechanism: This entails the use of chemical solutions like glycolic acid or salicylic acid that can help peel off the outer layer of skin thereby improving acne lesions (Zaenglein et al., 2016).

● Benefits: This includes comedonal acne treatment as well as improving texture complexion (Bhate & Williams, 2013).

c. Extraction and Drainage

● Mechanism: These include removal through physical means by a dermatologist using sterile instruments like comedones plus cysts (Harper & Thiboutot, 2016)

● Benefits: Brings instant relief from clogged pores hence minimizing scarring when done by a professional (Williams et al., 2012).

3.2 Home Acne Treatment

Managing acne or adjunctive therapies for more severe cases can be done at home. They include over the counter (OTC) products, natural remedies, and lifestyle modifications.

3.2.1 Over-the-Counter Products

OTC products, that are usually accessible and affordable, provide opportunities for management of early stage of acne. Some of the examples of these OTC products includes, but are not limited to;

a. Salicylic Acid

● Mechanism: A BHA penetrates the pores, exfoliating skin, reducing sebum production and preventing pore clogging (Bhate & Williams, 2013).

● Products: They come in the form of cleanser toner spot treatments with concentrations ranging from 0.5% to 2% (Zaenglein et al., 2016).

b. Benzoyl Peroxide

● Usage: These appear in various forms like cleansers, gels creams at different strengths (Harper & Thiboutot, 2016).

● Considerations: May cause dryness and irritation therefore it is preferred to start with a lower concentration then increase gradually up to tolerance level (Williams et al., 2012).

c. Alpha Hydroxy Acids (AHAs)

Examples: Glycolic acid, lactic acid.

● Mechanism: Promote the shedding of dead skin cells which leads to better texture and tone (Zaenglein et al., 2016).

● Products: These acids can be found in serum masks peels having different percentages ideal for home use ranging between five to ten percent (Bhate & Williams, 2013).

d. Niacinamide

● Mechanism: One type of Vitamin B3 that has anti-inflammatory activities and assists in reducing production of sebum (Gollnick & Krautheim, 2003).

● Usage: This is found in serums as well as creams mixed with other active ingredients for better performance (Zaenglein et al., 2016).

3.2.2 Natural Remedies

These remedies are commonly used in addition to traditional acne treatments; some have scientific support, while others are based on personal experiences (Fox et al., 2016).

a. Tea Tree Oil

● Mechanism: Has properties that prevent growth of bacteria and reduce inflammation (Williams et al., 2012).

● Usage: It should be blended with carrier oil such as jojoba oil or coconut oil before it is applied on the skin to avoid irritation (Harper & Thiboutot, 2016).

b. Aloe Vera

● Mechanism: Reduces inflammation when applied topically thereby improving wound healing process due to its antimicrobial effect (Bhate & Williams, 2013).

It is recommended to apply pure aloe vera gel directly to the affected areas or utilize products incorporating aloe vera as an ingredient (Zaenglein et al., 2016).

c. Honey

● Mechanism: It has natural antibacterial properties and can aid in wound healing (Gollnick & Krautheim, 2003).

● Application: It can be used topically as face mask or spot treatment particularly for inflamed acne lesions (Williams et al., 2012).

3.2.3 Lifestyle Modifications

Lifestyle adjustments can drastically change acne by reducing triggers and overall skin health support.

a. Diet

● Foods to Avoid: White bread, sugary snacks (e.g., high-glycemic foods) can worsen acne (Zaenglein et al., 2016).

● Foods to Include: Skin health is promoted by antioxidants such as blueberries and green tea, omega-3 fatty acids found in walnuts and fish, nuts and seeds that are rich in zinc (Harper & Thiboutot, 2016).

b. Stress Management

● Techniques: Combat stress via regular exercise, yoga or meditation to avoid triggering or worsening acne (Bhate & Williams, 2013).

● Benefits: Acne improves with stress management but also the general wellbeing of an individual (Zaenglein et al., 2016).

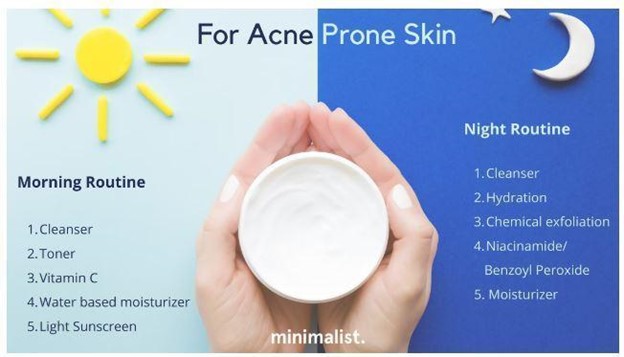

c. Daily Skincare Regimen

1. Cleansing: Use mild non-comedogenic cleanser twice daily to get rid of dirt, oil and make up from the face.

2. Treatment: Apply salicylic acid or benzoyl peroxide that acts as targeted treatments on the affected areas.

3. Moisturizing: To maintain barrier function and skin hydration use a lightweight non-comedogenic moisturizer.

4. Sun Protection: Prevention of UV damage to the skin requires application of broad-spectrum sunscreen with an SPF of at least 30 every day (Williams et al., 2012).

Figure 5: Basic Skincare Routine (source: beminimalist.co)

4. The Role of Nurses in Acne Management

Dealing with acne involves a concerted effort among dermatologists, general practitioners and now more frequently the nurses. In Finland, nurses’ involvement in acne management has advanced significantly, reflecting the shifts in healthcare provision and the increasing need to meet the rising requests for dermatological care. (Leino & Aaltonen, 2018)

The article is mainly focusing on the responsibilities of nurses in the management of acne in Finland. Generally, the holistic approach to acne management involves nurses who are concerned with identifying, educating, and supporting patients to enhance treatment outcomes. Nurses play key roles such as education of patients and provision of direct care (Koskinen & Järvinen, 2019).

In addition, operating nurses run clinics as well as incorporate teledermatology services as part of their involvement in the key area of acne treatment. As vital players between medical treatment and patient understanding, nurses also take part in making sure that patients have access to effective management for acne (Virtanen & Lähde, 2021).

4.1 Nurse-Led Clinics & Teledermatology

The establishment of nurse-led clinics in Finland is a major stride towards improving acne and various other dermatological conditions. This nurse led clinics are located amongst healthcare settings across the country, such as primary healthcare centers, hospitals and specialized outpatient clinics, occupational health services, community health centers in rural areas (Koskinen & Järvinen, 2019) and school health services (Kallio & Pietilä, 2018).

According to Koskinen and Järvinen (2019), these clinics enable nurses to independently manage cases of early stage of acne based on laid down protocols. This model has improved accessibility of dermatology services by reducing waiting time, ensuring that patients are seen within the shortest time possible, thereby improving patient satisfaction.

In the nurse-led clinic setting, nurses carry out initial assessments, educate, and formulate treatment plans about individuals suffering from acne. They can also help to educate the patients on prescribed specific drugs like topical treatments as directed by the dermatologist. With this arrangement, dermatologists have more time for complicated cases while ensuring that all patients receive the required attention (Koskinen & Järvinen, 2019).

Comprehensive training programs and professional development opportunities enjoyed by nurses on the treatment of acne are some of the reasons behind the success of nurse-led clinics in Finland (Salminen et al., 2016). The most effective care can be achieved through such measures that give nurses knowledge on how they can deal with common skin conditions including what causes acne or how to get rid of acne fast but not overnight among others. Moreover, this allows better patient outcomes when used in combination with well-established practice guidelines which ensure that every one of the patient adheres to such guidelines regardless (Lahtinen et al., 2014).

In Finland, teledermatology has become an invaluable tool in addressing dermatological diseases especially among those who live in the remote or underserved areas. The nurse plays a critical role in ensuring that teledermatology is well implemented since they are usually the first point of contact for patients and facilitate the remote consultation process (Virtanen & Lähde, 2021). Nurses in Finland typically conduct initial consultations with patients, collect relevant medical histories and take high resolution pictures of skin disease conditions as discussed by Virtanen & Lähde (2021). These images are then transmitted to dermatologists who review them and come up with treatment plans from far away. This model of care has been found effective especially in Finland where physical access to specialized dermatological services may be hampered by geographical distance (Virtanen & Lähde, 2021).

Nurses’ participation in teledermatology enhances patient’s access to care, as well as guaranteeing accurate diagnosis and treatment on time. The success of teledermatology services greatly depends on nurses’ ability to do comprehensive evaluations and communicate well with patients and dermatologists. Moreover, they help patients to get accustomed to treatment plans including proper use of drugs obtained from dermatologists as well as provision of appropriate information for skin care (Virtanen & Lähde, 2021).

4.2 Role of Nurses in the Management of Acne in Finland

4.2.1 Dermatological Care

In Finland, there has been a shift in the healthcare system towards specialized roles for nurses, especially in dermatology. The initial assessment and management of chronic skin conditions like acne are increasingly becoming the responsibility of nurses. This move is aimed at maximizing healthcare resources and ensuring patients get services on time as explained by Leino and Aaltonen (2018). Generally, dermatologists often have difficulty providing comprehensive care to all patients with acne due to high patient volumes. Involving more nurses actively in dermatological care can improve health service delivery efficiency and outcomes (Leino & Aaltonen, 2018).

Nursing professionals in Finland undergo specialized training in dermatology at the university of applied sciences (Salminen et al., 2016), on the job training and workshops (Virtanen & Lähde, 2021) and collaborative programs with dermatologists (Ranta & Suominen, 2020), which then prepares them to address common cutaneous disorders. They learn about different ways of acne pathophysiology, treatment, as well as psychosocial effects on victims. Consequently, nurses can do extensive evaluations, create nursing plans, and oversee progress during treatment; thus, serving as an indispensable support system for both patients and dermatologists (Ranta & Suominen, 2020).

4.2.1.1 Initial assessment & History Taking

As nurses conduct an in-depth assessment of acne patients, the assessment of its severity and factors which may affect its treatment must be identified. The assessment may include understanding the type of skin the patients have, habit of the patient as well as lifestyle, and patient response to previous treatment. This information is used to have a specific or personalized care plan that can factor in both the physical symptoms and emotional effect of acne on the patient and also make sure the treatment is appropriate for the patient (Leino & Aaltonen, 2018). This early diagnosis is important in the establishment of the correct measure to take which may result in use of counter products or consultancy from dermatologists in severe cases (Leino & Aaltonen, 2018). Gathering a comprehensive history of the patient including onset, duration, previous treatments among others helps in identifying potential triggers thereby enabling personalized treatment plans. (Harper & Thiboutot, 2016).

4.2.1.2 Personalized acne care plan

As nursing plans are critical in the planning of every patient treatment and care, nurses ensure to make personalized care plans for acne patients as well. These plans would include recommendations for topical treatments, medications, modifications of lifestyle and patient education. These plans also contain how to manage the condition effectively, diet tips, management of stress, skincare techniques, which goal is to improve patients’ skincare health and follow up to treatment (Koskinen & Järvinen, 2019).

4.2.1.3 Treatment & monitoring

Nurses play a crucial part in the treatment of acne by the administration of topical or oral therapies such as retinoids and antibiotics and as well as helping in procedures like light therapy or chemical pels (Gollnick et al., 2016). Acne treatment most times requires a thorough treatment process thereby requiring the monitoring of the patient’s progress in order to achieve the effectiveness of the treatment. This requires continuous assessment of the patient’s skin condition on a regular basis, adjustment of care plans if needed and provision of continual support. By monitoring the patient’s treatment , identification of any complication can easily be identified by the nurse and addressed immediately, thereby avoiding any mishap in patients’ care (Leino & Aaltonen, 2018; Koskinen & Järvinen, 2019).

4.2.1.4 Referral and Collaboration

In case there is need, they can refer patients for further evaluation and treatment from dermatologists or other specialists; while working collaboratively with the health care team for effective delivery (Williams et al., 2012).

4.2 Patient Education and Learning

One of the most vital duties of nurses in acne monitoring is patient education and learning. Efficient monitoring of acne usually needs clients to follow complicated therapy regimens, consisting of making use of topical or dental drugs, skincare regimens and lifestyle alterations (Ranta & Suominen, 2020). As Ranta and Suominen (2020) emphasized, nurses are well-positioned to give this education and learning in a fashion that comes handy and reasonable to individuals. In Finland, nurses are commonly the first people to get in touch with people looking for acne therapy or treatment, especially in medical care setups. They play a vital part in enlightening patients concerning the sources of acne, the value of complying with suggested therapies as well as the effect of other aspects such as diet regimen, anxiety, skin health and wellness. This education and learning are not just essential for handling the physical signs and symptoms of acne but necessary for resolving the psychological and mental effects of the problem.

The research by Ranta and Suominen (2020) also reported that education and learning regarding acne administration given by nurses lead to a substantial improvement in individual adherence to therapy routines. Clients that comprehended the reasoning behind their therapy strategies were more probable to follow up with them leading to far better end results. In addition, nurses use continuous assistance as well as motivation in aiding people to follow the frequently challenging routine of handling a persistent acne problem.

4.3 Providing Support and Encouragement

Nurses offer emotional support and encouragement, which could prove invaluable for patients struggling with psychological effects caused by acne. This assistance may include:

● Building Rapport: Trustworthy relationships formed between doctors/nurses and patients encourage openness in communication hence improve adherence to treatment (Williams et al., 2012).

● Monitoring Progress: Nurses have a chance to evaluate treatment effectiveness through regular follow-ups thus being able to offer necessary modifications where required besides providing ongoing support (Zaenglein et al., 2016).

● Encouraging Self-Management: Patient involvement in their own healthcare through education on self-care practices around managing acne has been shown to have positive outcomes in this area (Harper & Thiboutot, 2016).

5. Challenges and Future Directions

Although the extent of nurses´ involvement in the treatment of acne in Finland has risen to a higher level in recent years, there are still some obstacles. One of these obstacles has to do with establishing that all nurses have the requisite knowledge, such as proper training at nursing university or schools and tools in order to offer good skin related care (Kallio & Pietilä, 2018). Another issue is the identification of the type of acne and assessment of what stage the acne might have progressed through teledermatology.

However, the Finnish Student Health student service (YTHS) has had several discussions on the assessment and identification of different types of acne and its severity though the use of teledermatology, which gives an overview of how technology can be integrated into daily procedures of dermatological care and the importance of continuous training for nurses and other healthcare professionals (FSHS, 2021). It is in this view that teledermatology and other similar tools and their various components of application will continue to improve over time and will therefore call for constant training of the nurses.

Furthermore, development of more nurse-led clinics implies further assessment of the effectiveness of such practice and modification based on the patients’ needs, especially for those who are suffering from different severity of acne or other severe forms of skin disorders. Overall, while nurse-led clinics show promise, their effectiveness must be regularly assessed to adapt to patient requirements.

Conclusion

The Management of acne may require an approach that combines medical treatments and home remedies. For severe cases advanced treatments are available in healthcare facilities, as early cases of acne can benefit from at-home remedies and lifestyle adjustments.

Nurses play a key role in educating and supporting patients with acne, helping them understand and adhere to their treatment plans. By being aware of the options, individuals can make choices and collaborate with healthcare professionals to achieve clearer and healthier skin.

Nurses have a central and influential part in care of acne in Finland and are thus key players in dermatological care. Besides the early intervention, input and support, nurses have a key role to play in enhancing the status of acne treatment in Finland through case management and implementation of elements such as nurses’ clinics and tele-dermatology.

In future, with the dynamic changes happening to the healthcare system, the roles played by nurses in dermatology are set to increase even more to bring in more benefits to patients in Finland and as such more training, classroom teaching and seminars should be encouraged for nursing students, nurses and healthcare workers in general in the subject of skin care and acne recognition, in order to mitigate the severity of acne in patients and as this can also help to reduce cost in healthcare.

Author:

Kingsley C Aliche, Savonia University of Applied Sciences

References:

1. Bhate, K., & Williams, H. C. (2013). Epidemiology of acne vulgaris. British Journal of Dermatology, 168(3), 474-485. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.12146

2. Beminimalist. (n.d.). Skincare routine for oily acne-prone skin. Beminimalist. https://beminimalist.co/blogs/skin-care/skincare-routine-for-oily-acne-prone-skin

3. Fox, L., Csongradi, C., Aucamp, M., du Plessis, J., & Gerber, M. (2016). Treatment modalities for acne. Molecular and Cellular Therapies, 4(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40348-016-0059-6

4. Gollnick, H. P., & Krautheim, A. (2003). Topical therapy in acne. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology, 17(2), 170-176. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1468-3083.2003.00580.x

5. Gollnick, H., et al. (2016). “Management of acne: a report from a global alliance to improve outcomes in acne.” Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 74(5), 945-973. This source discusses comprehensive approaches to acne treatment and management protocols.

6. Harper, J. C., & Thiboutot, D. M. (2016). Pathogenesis of acne: Recent research advances. Advances in Dermatology and Allergology/Postępy Dermatologii i Alergologii, 33(4), 303-307. https://doi.org/10.5114/ada.2016.60812

7. Kallio, J., & Pietilä, A. M. (2018). School health services in Finland: Nurses’ role in promoting student health. Journal of School Nursing, 34(1), 73-81. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059840517722761

8. Koskinen, S., & Järvinen, A. (2019). Nurse-led acne clinics: Enhancing dermatological care in Finland. Scandinavian Journal of Nursing, 5(3), 88-94. https://doi.org/10.16962/sjns.63113

9. Lahtinen, P., Leino-Kilpi, H., & Salminen, L. (2014). Continuing education in nursing: The impact on professional practice. Nurse Education Today, 34(4), 553-558. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2013.07.011

10. Leino, M., & Aaltonen, O. (2018). The expanding role of nurses in dermatological care in Finland. Journal of Dermatological Nursing, 10(2), 45-52. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdn.12155

11. Miettinen, T. (2016). Occupational health services in Finland: The role of nurses in providing preventive care. Finnish Journal of Occupational Health, 28(2), 112-119. https://doi.org/10.2478/sfjo-2016-0007

12. Ranta, H., & Suominen, T. (2020). Impact of nurse-led education on acne management: A Finnish study. Journal of Nursing Education and Practice, 10(11), 120-127. https://doi.org/10.5430/jnep.v10n11p120

13. Salminen, L., Lindqvist, R., Eriksson, E., & Fagerström, L. (2016). Nurse education in Finland: Learning outcomes and quality assurance. International Nursing Review, 63(1), 78-84. https://doi.org/10.1111/inr.12240

14. Tan, J. K. L., & Bhate, K. (2015). A global perspective on the epidemiology of acne. British Journal of Dermatology, 172(s1), 3-12. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.13562

15. Virtanen, E., & Lähde, M. (2021). Teledermatology in Finland: The critical role of nurses in remote acne management. Telemedicine and e-Health, 27(5), 547-553. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2020.0286

16. Williams, H. C., Dellavalle, R. P., & Garner, S. (2012). Acne vulgaris. The Lancet, 379(9813), 361-372. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60747-4

17. Zaenglein, A. L., Pathy, A. L., Schlosser, B. J., Alikhan, A., Baldwin, H. E., Berson, D. S., … & Zouboulis, C. C. (2016). Guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 74(5), 945-973. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2015.12.037

18. Finnish Student Health Service (FSHS). (2021). Teledermatology services at FSHS. Finnish Student Health Service.https://www.yths.fi/en/services/specialist-services/teledermatology/4